Stomach cancer

| Gastric cancer | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

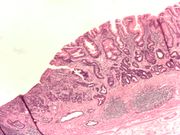

A suspicious stomach ulcer that was diagnosed as cancer on biopsy and resected. Surgical specimen. |

|

| ICD-10 | C16. |

| ICD-9 | 151 |

| OMIM | 137215 |

| DiseasesDB | 12445 |

| eMedicine | med/845 |

| MeSH | D013274 |

Gastric cancer can develop in any part of the stomach and may spread throughout the stomach and to other organs; particularly the esophagus, lungs, lymph nodes, and the liver. Stomach cancer causes about 800,000 deaths worldwide per year.[1]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

Stomach cancer is often asymptomatic or causes only nonspecific symptoms in its early stages. By the time symptoms occur, the cancer has often reached an advanced stage (see below), one of the main reasons for its poor prognosis. Stomach cancer can cause the following signs and symptoms:

Early

- Indigestion or a burning sensation (heartburn)

- Loss of appetite, especially for meat

Late

- Abdominal pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Bloating of the stomach after meals

- Weight loss

- Weakness and fatigue

- Bleeding (vomiting blood or having blood in the stool) which will appear as black. This can lead to anemia.

- Dysphagia; this feature suggests a tumor in the cardia or extension of the gastric tumor in to the esophagus.

These can be symptoms of other problems such as a stomach virus, gastric ulcer or tropical sprue. Diagnosis should be done by a gastroenterologist or an oncologist.

Causes

Infection by Helicobacter pylori is believed to be the cause of most stomach cancer while autoimmune atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and various genetic factors are associated with increased risk levels. The clinical medical reference the Merck Manual states that diet plays no role in the genesis of stomach cancer.[2] However, the American Cancer Society lists the following dietary risks, and protective factors, for stomach cancer: "smoked foods, salted fish and meat, and pickled vegetables (appear to increase the risk of stomach cancer.) Nitrates and nitrites are substances commonly found in cured meats. They can be converted by certain bacteria, such as H pylori, into compounds that have been found to cause stomach cancer in animals. On the other hand, eating fresh fruits and vegetables that contain antioxidant vitamins (such as A and C) appears to lower the risk of stomach cancer."[3] A December 2009 article in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found a statistically significant inverse correlation between higher adherence to a Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and stomach cancer.[4]

In more detail, H. pylori is the main risk factor in 65–80% of gastric cancers, but in only 2% of such infections.[5] Approximately ten percent of cases show a genetic component.[6] In Japan and other countries bracken consumption and spores are correlated with incidence of stomach cancer, though causality has yet to be established.[7]

A very important but preventable cause of gastric cancer is tobacco smoking. Smoking increases the risk of developing gastric cancer considerably; from 40% increased risk for current smokers to 82% increase for heavy smokers which is about twice the risk for non-smoking population. Gastric cancers due to smoking mostly occur in upper part of stomach near esophagus[8][9][10] Another lifestyle cause of gastric cancer beside smoking is consumption of alcohol.[11][12][13] Alcohol as cause of cancer along with tobacco smoking as cause of cancer increase the risk of developing other cancers as well.

Gastric cancer shows a male predominance in its incidence as up to three males are affected for every female. Estrogen may protect women against the development of this cancer form.[14] A very small percentage of diffuse-type gastric cancers (see Histopathology below) are thought to be genetic. Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer (HDGC) has recently been identified and research is ongoing. However, genetic testing and treatment options are already available for families at risk.[15]

Some researchers [16] showed a correlation between Iodine deficiency or excess, iodine-deficient goitre and gastric cancer; a decrease of the incidence of death rate from stomach cancer after implementation of the effective I-prophylaxis was reported too.[17] The proposed mechanism of action is that iodide ion can function in gastric mucosa as an antioxidant reducing species that can detoxify poisonous reactive oxygen species, such as hydrogen peroxide. The International Cancer Genome Consortium is leading efforts to map stomach cancer's complete genome.

Diagnosis

To find the cause of symptoms, the doctor asks about the patient's medical history, does a physical exam, and may order laboratory studies. The patient may also have one or all of the following exams:

- Gastroscopic exam is the diagnostic method of choice. This involves insertion of a fiber optic camera into the stomach to visualize it.

- Upper GI series (may be called barium roentgenogram)

- Computed tomography or CT scanning of the abdomen may reveal gastric cancer, but is more useful to determine invasion into adjacent tissues, or the presence of spread to local lymph nodes.

Abnormal tissue seen in a gastroscope examination will be biopsied by the surgeon or gastroenterologist. This tissue is then sent to a pathologist for histological examination under a microscope to check for the presence of cancerous cells. A biopsy, with subsequent histological analysis, is the only sure way to confirm the presence of cancer cells.

Various gastroscopic modalities have been developed to increased yield of detect mucosa with a dye that accentuates the cell structure and can identify areas of dysplasia. Endocytoscopy involves ultra-high magnification to visualize cellular structure to better determine areas of dysplasia. Other gastroscopic modalities such as optical coherence tomography are also being tested investigationally for similar applications.[18]

A number of cutaneous conditions are associated with gastric cancer. A condition of darkened hyperplasia of the skin, frequently of the axilla and groin, known as acanthosis nigricans, is associated with intra-abdominal cancers such as gastric cancer. Other cutaneous manifestations of gastric cancer include tripe palms (a similar darkening hyperplasia of the skin of the palms) and the sign of Leser-Trelat, which is the rapid development of skin lesions known as seborrheic keratoses.[19]

Histopathology

_H&E_magn_400x.jpg)

.jpg)

- Gastric adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from glandular epithelium of the gastric mucosa. Stomach cancers are overwhelmingly adenocarcinomas (90%).[20] Histologically, there are two major types of gastric adenocarcinoma (Lauren classification): intestinal type or diffuse type. Adenocarcinomas tend to aggressively invade the gastric wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae, the submucosa, and thence the muscularis propria. Intestinal type adenocarcinoma tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Often, it associates intestinal metaplasia in neighboring mucosa. Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism and mucosecretion, adenocarcinoma may present 3 degrees of differentiation: well, moderate and poorly differentiate. Diffuse type adenocarcinoma (mucinous, colloid, linitis plastica, leather-bottle stomach) Tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus which is delivered in the interstitium producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces). It is poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus at the purpley- "signet-ring cell".

- Around 5% of gastric carcinomas are lymphomas (MALTomas, or MALT lymphoma).[21]

- Carcinoid and stromal tumors may also occur.

Staging

If cancer cells are found in the tissue sample, the next step is to stage, or find out the extent of the disease. Various tests determine whether the cancer has spread and, if so, what parts of the body are affected. Because stomach cancer can spread to the liver, the pancreas, and other organs near the stomach as well as to the lungs, the doctor may order a CT scan, a PET scan, an endoscopic ultrasound exam, or other tests to check these areas. Blood tests for tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) may be ordered, as their levels correlate to extent of metastasis, especially to the liver, and the cure rate.

Staging may not be complete until after surgery. The surgeon removes nearby lymph nodes and possibly samples of tissue from other areas in the abdomen for examination by a pathologist.

The clinical stages of stomach cancer are:[22][23]

- Stage 0. Limited to the inner lining of the stomach. Treatable by endoscopic mucosal resection when found very early (in routine screenings); otherwise by gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy without need for chemotherapy or radiation.

- Stage I. Penetration to the second or third layers of the stomach (Stage 1A) or to the second layer and nearby lymph nodes (Stage 1B). Stage 1A is treated by surgery, including removal of the omentum. Stage 1B may be treated with chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil) and radiation therapy.

- Stage II. Penetration to the second layer and more distant lymph nodes, or the third layer and only nearby lymph nodes, or all four layers but not the lymph nodes. Treated as for Stage I, sometimes with additional neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Stage III. Penetration to the third layer and more distant lymph nodes, or penetration to the fourth layer and either nearby tissues or nearby or more distant lymph nodes. Treated as for Stage II; a cure is still possible in some cases.

- Stage IV. Cancer has spread to nearby tissues and more distant lymph nodes, or has metastatized to other organs. A cure is very rarely possible at this stage. Some other techniques to prolong life or improve symptoms are used, including laser treatment, surgery, and/or stents to keep the digestive tract open, and chemotherapy by drugs such as 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, epirubicin, etoposide, docetaxel, oxaliplatin, capecitabine, or irinotecan.

The TNM staging system is also used.[24]

In a study of open-access endoscopy in Scotland, patients were diagnosed 7% in Stage I 17% in Stage II, and 28% in Stage III.[25] A Minnesota population was diagnosed 10% in Stage I, 13% in Stage II, and 18% in Stage III.[26] However in a high-risk population in the Valdivia province of southern Chile, only 5% of patients were diagnosed in the first two stages and 10% in stage III.[27]

Management

As with any cancer, treatment is adapted to fit each person's individual needs and depends on the size, location, and extent of the tumor, the stage of the disease, and general health. Cancer of the stomach is difficult to cure unless it is found in an early stage (before it has begun to spread). Unfortunately, because early stomach cancer causes few symptoms, the disease is usually advanced when the diagnosis is made. Treatment for stomach cancer may include surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy. New treatment approaches such as biological therapy and improved ways of using current methods are being studied in clinical trials.

Surgery

Surgery is the most common treatment and is the only hope of cure for stomach cancer. The surgeon removes part or all of the stomach, as well as the surrounding lymph nodes, with the basic goal of removing all cancer and a margin of normal tissue. Depending on the extent of invasion and the location of the tumor, surgery may also include removal of part of the intestine or pancreas. Tumors in the lower part of the stomach may call for a Billroth I or Billroth II procedure. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is a treatment for early gastric cancer (tumor only involves the mucosa) that has been pioneered in Japan, but is also available in the United States at some centers. In this procedure, the tumor, together with the inner lining of stomach (mucosa), is removed from the wall of the stomach using an electrical wire loop through the endoscope. The advantage is that it is a much smaller operation than removing the stomach. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a similar technique pioneered in Japan, used to resect a large area of mucosa in one piece. If the pathologic examination of the resected specimen shows incomplete resection or deep invasion by tumor, the patient would need a formal stomach resection.

Surgical interventions are currently curative in less than 40% of cases, and, in cases of metastasis, may only be palliative.

Chemotherapy

The use of chemotherapy to treat stomach cancer has no established standard of care. Unfortunately, stomach cancer has not been especially sensitive to these drugs until recently, and historically served to palliatively reduce the size of the tumor and increase survival time. Some drugs used in stomach cancer treatment include: 5-FU (fluorouracil), BCNU (carmustine), methyl-CCNU (Semustine), and doxorubicin (Adriamycin), as well as Mitomycin C, and more recently cisplatin and taxotere in various combinations. The relative benefits of these drugs, alone and in combination, are unclear.[28] Scientists are exploring the benefits of giving chemotherapy before surgery to shrink the tumor, or as adjuvant therapy after surgery to destroy remaining cancer cells. Combination treatment with chemotherapy and radiation therapy is also under study. Doctors are testing a treatment in which anticancer drugs are put directly into the abdomen (intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion). Chemotherapy also is being studied as a treatment for cancer that has spread, and as a way to relieve symptoms of the disease. The side effects of chemotherapy depend mainly on the drugs the patient receives.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) is the use of high-energy rays to damage cancer cells and stop them from growing. When used, it is generally in combination with surgery and chemotherapy, or used only with chemotherapy in cases where the individual is unable to undergo surgery. Radiation therapy may be used to relieve pain or blockage by shrinking the tumor for palliation of incurable disease

Multimodality therapy

While previous studies of multimodality therapy (combinations of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy) gave mixed results, the Intergroup 0116 (SWOG 9008) study[29] showed a survival benefit to the combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in patients with nonmetastatic, completely resected gastric cancer. Patients were randomized after surgery to the standard group of observation alone, or the study arm of combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Those in the study arm receiving chemotherapy and radiation therapy survived on average 36 months; compared to 27 months with observation.

Epidemiology

Stomach cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide with 930,000 cases diagnosed in 2002.[31] It is a disease with a high death rate (~800,000 per year) making it the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide after lung cancer.[1] It is more common in men and in developing countries.[31][32]

It represents roughly 2% (25,500 cases) of all new cancer cases yearly in the United States, but it is more common in other countries. It is the leading cancer type in Korea, with 20.8% of malignant neoplasms.

Metastasis occurs in 80-90% of individuals with stomach cancer, with a six month survival rate of 65% in those diagnosed in early stages and less than 15% of those diagnosed in late stages.

One in a million people under the age of 55 seeking medical attention for indigestion has stomach cancer [33] and one in 50 of all ages seeking medical attention for burping and indigestion have stomach cancer.[34] Out of 10 million people in the Czech Republic, only 3 new cases of stomach cancer in people under 30 years of age in 1999 were diagnosed.[35] Other studies show that less than 5% of stomach cancers occur in people under 40 years of age with 81.1% of that 5% in the age-group of 30 to 39 and 18.9% in the age-group of 20 to 29.[36]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Cancer (Fact sheet N°297)". World Health Organization. February 2009. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ↑ "Tumors of the GI Tract, Merck Manual (Professional)". Merck. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec02/ch021/ch021d.html. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ "What Are The Risk Factors For Stomach Cancer(Website)". American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/cri/content/cri_2_4_2x_what_are_the_risk_factors_for_stomach_cancer_40.asp. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ "Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort study (Professional)". American Society for Clinical Nutrition. http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/short/ajcn.2009.28209v1. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the fourth Global Vaccine Research Forum". Initiative for Vaccine Research team of the Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. WHO. April 2004. http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/documents/en/gvrf2003.pdf. Retrieved 2009-05-11. "Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer…"

- ↑ Lee HJ, Yang HK, Ahn YO (2002). "Gastric cancer in Korea". Gastric Cancer : Official Journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association 5 (3): 177–82. doi:10.1007/s101200200031. PMID 12378346.

- ↑ Alonso-Amelot ME, Avendaño M (March 2002). "Human carcinogenesis and bracken fern: a review of the evidence". Current Medicinal Chemistry 9 (6): 675–86. PMID 11945131. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CMC/2002/00000009/00000006/0004C.SGM. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/reprint/50/21/7084.pdf

- ↑ http://www.cancer.org/docroot/cri/content/cri_2_4_2x_what_are_the_risk_factors_for_stomach_cancer_40.asp

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9259392

- ↑ http://jjco.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/38/1/8

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/bjc/journal/v97/n5/full/6603893a.html

- ↑ http://www.hmc.psu.edu/healthinfo/s/stomachcancer.htm

- ↑ Chandanos, Evangelos (December 2007) (PDF). Estrogen in the development of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma. Karolinska Institutet. ISBN 978-91-7357-370-2. http://diss.kib.ki.se/2007/978-91-7357-370-2/thesis.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ Brooks-Wilson AR, Kaurah P, Suriano G, et al. (2004). "Germline E-cadherin mutations in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: assessment of 42 new families and review of genetic screening criteria". J. Med. Genet. 41 (7): 508–17. doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.018275. PMID 15235021.

- ↑ Venturi S, Venturi A, Cimini D, Arduini C, Venturi M, Guidi A (January 1993). "A new hypothesis: iodine and gastric cancer". Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2 (1): 17–23. PMID 8428171.

Venturi S, Venturi M (April 1999). "Iodide, thyroid and stomach carcinogenesis: evolutionary story of a primitive antioxidant?". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 140 (4): 371–2. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1400371. PMID 10097259. http://eje-online.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10097259.

Venturi S, Donati FM, Venturi A, Venturi M, Grossi L, Guidi A (January 2000). "Role of iodine in evolution and carcinogenesis of thyroid, breast and stomach". Adv Clin Path 4 (1): 11–7. PMID 10936894.

Abnet CC, Fan JH, Kamangar F, et al. (September 2006). "Self-reported goiter is associated with a significantly increased risk of gastric noncardia adenocarcinoma in a large population-based Chinese cohort". Int. J. Cancer 119 (6): 1508–10. doi:10.1002/ijc.2199310.1002/ijc.21993. PMID 16642482.

Behrouzian R, Aghdami N (November 2004). "Urinary iodine/creatinine ratio in patients with stomach cancer in Urmia, Islamic Republic of Iran". East. Mediterr. Health J. 10 (6): 921–4. PMID 16335780.

Gulaboglu M, Yildiz L, Celebi F, Gul M, Peker K (2005). "Comparison of iodine contents in gastric cancer and surrounding normal tissues". Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 43 (6): 581–4. doi:10.1515/CCLM.2005.101. PMID 16006252. http://www.reference-global.com/doi/abs/10.1515/CCLM.2005.101. - ↑ Gołkowski F, Szybiński Z, Rachtan J, et al. (August 2007). "Iodine prophylaxis--the protective factor against stomach cancer in iodine deficient areas". Eur J Nutr 46 (5): 251–6. doi:10.1007/s00394-007-0657-8. PMID 17497074.

- ↑ Inoue H, Kudo SE, Shiokawa A (January 2005). "Technology insight: Laser-scanning confocal microscopy and endocytoscopy for cellular observation of the gastrointestinal tract". Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2 (1): 31–7. doi:10.1038/ncpgasthep0072. PMID 16265098.

- ↑ Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Pagano M, Gandolfo S (July 2004). "Oral acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and sign of leser-trélat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma". Int. J. Dermatol. 43 (7): 530–2. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02159.x. PMID 15230897.

- ↑ Kumar, et. al: Pathologic Basis of Disease: 8th ed., page 784. Saunders Elsevier, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

- ↑ Kumar, et. al: Pathologic Basis of Disease: 8th ed., page 786. Saunders Elsevier, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

- ↑ "Detailed Guide: Stomach Cancer Treatment Choices by Type and Stage of Stomach Cancer". American Cancer Society. 2009-11-03. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/cri/content/cri_2_4_4x_treatment_choices_by_type_and_stage_of_stomach_cancer_40.asp.

- ↑ Guy Slowik (2009-10). "What Are The Stages Of Stomach Cancer?". ehealthmd.com. http://www.ehealthmd.com/library/stomachcancer/STC_stages.html.

- ↑ "Detailed Guide: Stomach Cancer: How Is Stomach Cancer Staged?". American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_3X_How_is_stomach_cancer_staged_40.asp?sitearea=.

- ↑ Error: No PMID specified!

- ↑ Sarah J. Crane et al. (2008-10). "Survival Trends in Patients With Gastric and Esophageal Adenocarcinomas: A Population-Based Study". Mayo Clin Proc. 83 (10): 1087–1094. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2597541/table/T1/.

- ↑ Katy Heise et al. (2009-04-21). "Incidence and survival of stomach cancer in a high-risk population of Chile". World J Gastroenterol. 15 (15): 1854–1862. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.1854. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2670413/table/T2/.

- ↑ Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Verdecchia L, et al. (April 2007). "Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: across the years for a standard of care". Expert Opin Pharmacother 8 (6): 797–808. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.6.797. PMID 17425475. http://www.expertopin.com/doi/abs/10.1517/14656566.8.6.797.

- ↑ Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al. (2001). "Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction". N. Engl. J. Med. 345 (10): 725–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa010187. PMID 11547741.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005). "Global cancer statistics, 2002". CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians 55 (2): 74–108. doi:10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. PMID 15761078.

- ↑ "Are the number of cancer cases increasing or decreasing in the world?". WHO Online Q&A. WHO. 1 April 2008. http://www.who.int/features/qa/15/en/index.html. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ↑ "Stomach cancer - symptoms, causes and treatment". Bupa. 2007-05-02. http://hcd2.bupa.co.uk/fact_sheets/html/stomach_cancer.html#3. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ↑ "Stomach cancer symptoms: Cancer Research UK". CancerHelp UK. 2007-06-15. http://www.cancerhelp.org.uk/help/default.asp?page=3897. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ↑ Simsa J, Leffler J, Hoch J, Linke Z, Pádr R (2004). "Gastric cancer in young patients--is there any hope for them?" (PDF). Acta Chirurgica Belgica 104 (6): 673–6. PMID 15663273. http://www.belsurg.org/imgupload/RBSS/simsa.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ "Gastric Cancer in Young Adults". Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia - Volume 46 n°3 Jul/Ago/Set 2000. Inca.gov.br. 2000. http://www.inca.gov.br/rbc/n_46/v03/english/article6.html. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

External links

- National Cancer Institute Gastric cancer treatment guidelines

- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer

- No Stomach For Cancer | Be Strong Hearted is a source of information and support for Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer and carriers of the CDH1 gene mutation and their families/friends.

- "Stomach Cancer. In: Iodine Deficiency: studies by dr. Sebastiano Venturi (Italy)". http://web.tiscali.it/iodio/. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||